Manifest series

I am an artist and educator. These two roles have always shared priority in my professional life. These roles inform one another and fuel my drive to succeed in each. The work I’ve produced here is a testament to my pursuit of excellence as both an artist and an educator. The enduring effort of my work is to challenge the field of metalsmithing and our understanding of the hand-made while educating the uninitiated.

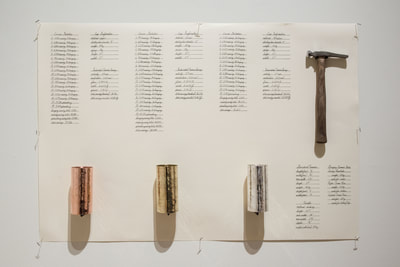

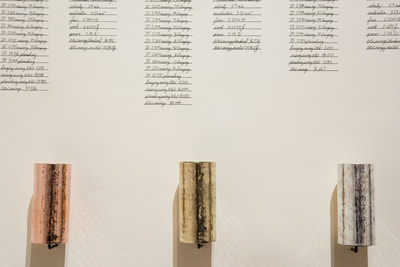

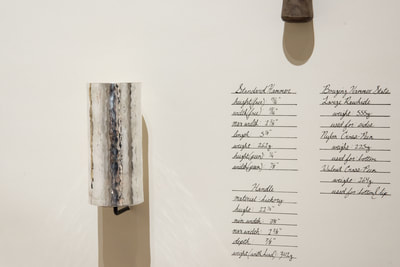

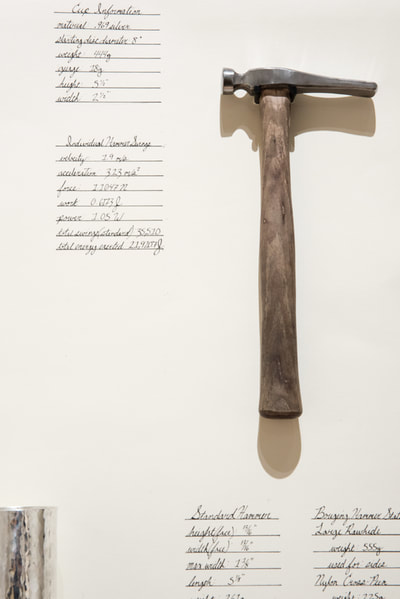

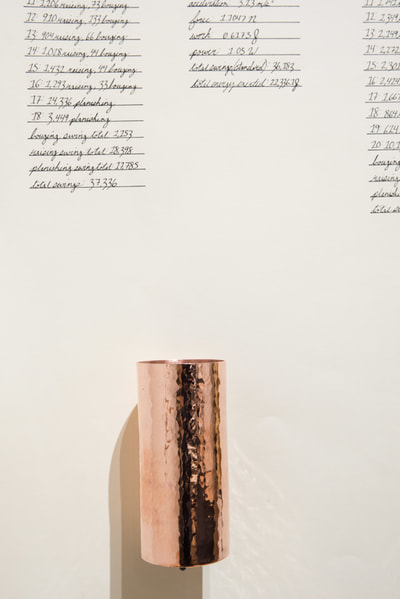

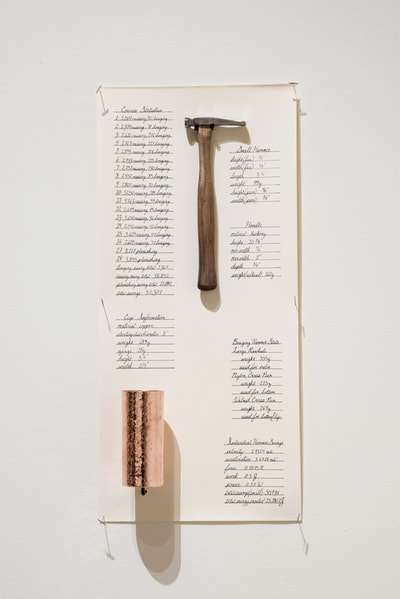

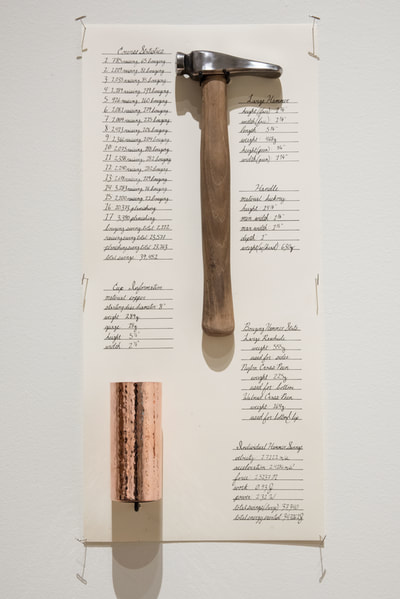

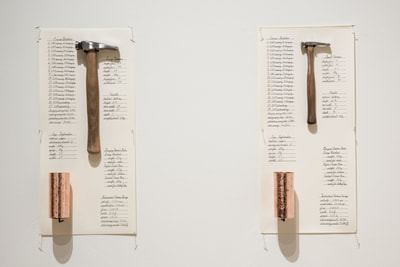

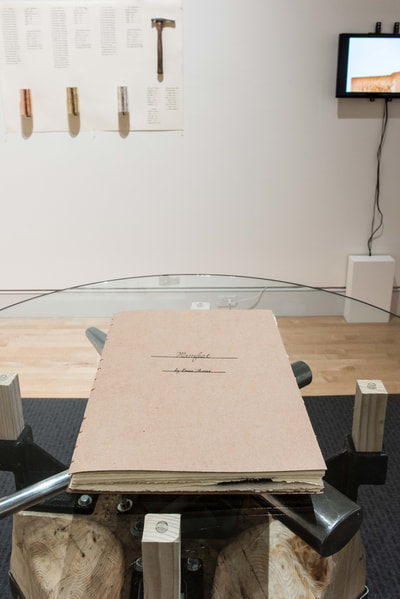

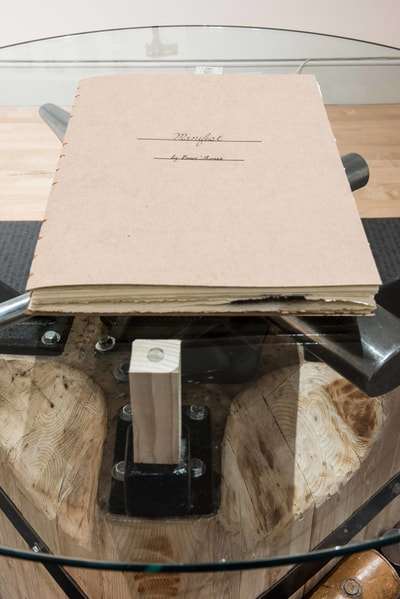

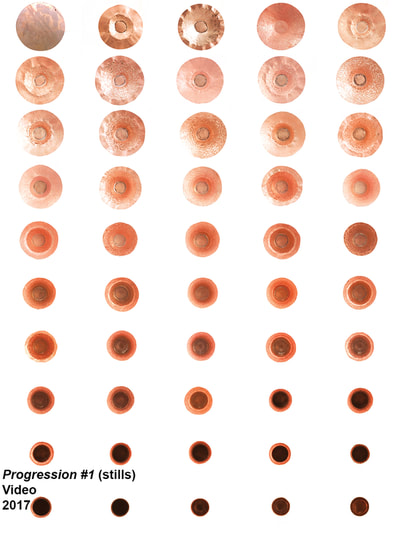

My research is influenced by traditional metalsmithing techniques within the realm of handmade objects. Questioning how people view and interact with handmade objects, my research has led me to utilize the approach of Relational Aesthetics to provide individuals with the opportunity to break away from the constraints of the pedestal as they engage in the work in an intimate and tactile fashion. As I create a setting in which participants are actively encouraged to manipulate and engage with the work, I become the catalyst for the living model of handmade objects in our everyday life. As these objects accumulate evidence of use through the accrual of dents, scratches, and tarnishing, they begin to catalogue the life of a handmade object after it leaves the hands of its creator. Further research on the life of a handmade object has led to the detailed and arduous cataloguing of all events and tools that go into the making of these objects. The visual display of labor, repetition, and technical mastery helps place into context what a handmade object can represent. From an inventory of tools used in the process of making to the meticulous counting of every hammer swing, this progression of making manifests into the form of physical objects, thorough logs of thousands of hammer swings, and video installations of the subtle movements the metal makes. Together, my research has led to the educational display of the lifespan of handmade metal objects as participants question their value and role today.

My research is influenced by traditional metalsmithing techniques within the realm of handmade objects. Questioning how people view and interact with handmade objects, my research has led me to utilize the approach of Relational Aesthetics to provide individuals with the opportunity to break away from the constraints of the pedestal as they engage in the work in an intimate and tactile fashion. As I create a setting in which participants are actively encouraged to manipulate and engage with the work, I become the catalyst for the living model of handmade objects in our everyday life. As these objects accumulate evidence of use through the accrual of dents, scratches, and tarnishing, they begin to catalogue the life of a handmade object after it leaves the hands of its creator. Further research on the life of a handmade object has led to the detailed and arduous cataloguing of all events and tools that go into the making of these objects. The visual display of labor, repetition, and technical mastery helps place into context what a handmade object can represent. From an inventory of tools used in the process of making to the meticulous counting of every hammer swing, this progression of making manifests into the form of physical objects, thorough logs of thousands of hammer swings, and video installations of the subtle movements the metal makes. Together, my research has led to the educational display of the lifespan of handmade metal objects as participants question their value and role today.

|

|

|

Thomas Bosse's carefully crafted hollow vessels bring joy to their users. While it is tempting to admire such artistry from afar, these are functional objects meant to be used. Indeed, it is precisely this history of use and creation that interests the artist most.

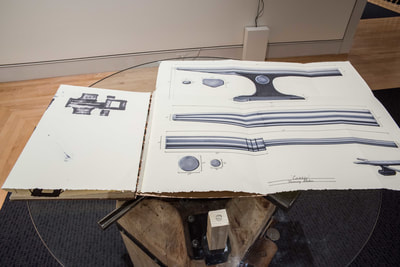

When his vessels are displayed in a gallery setting, Bosse turns our attention to how they were created. Executed in a variety of materials, the exhibited cups appear identical- a fact that attests to the artist's technical skill and ability to seamlessly recreate the same crafted object by hand. Next to these cups are diagrams cataloguing the process by which they were made: which hammer was used, the hammer's weight, the energy necessitated by this weight, the angle at which the hammer was applied, how many hammer strokes were required. In this way, Bosse not only documents the object's beginnings, but also intimately ties himself to their inception, proclaiming the presence of the artist's hand.

If Bosse is interested in the prehistory of his vessels, he is equally invested in the lives these objects lead upon completion. Those who attended the opening reception of the MFA exhibition were met by a welcome sight: the BOSSE bar. Familiar to many because of its temporary presence a few months earlier on campus, the BOSSE bar served as a much needed respite after long classes, a place where students, professors, and other visitors mingled, periodically swapping cups to gleefully admire the cast metal dinosaurs surrounding the base of one cup or the mustache guard on top of another. Returning visitors fondly reminisced about their first cup, all while Bosse regaled them guests with stories, inspirations, and difficulties surrounding specific vessels. At the Georgia Museum of Art during the opening of the MFA thesis exhibition, visitors could imbibe at the BOSSE bar before and after visiting the show upstairs, where Bosse's cups and diagrams were exhibited amongst the work of his peers. More significant than the drink, though, is the vessel from which it is drunk: a tall vessel of pewter complete with handle, resembling those displayed in the museum. For Bosse, this marks an important continuation of the vessels' lives. Rather than relegate these meticulously crafted functional objects to a pedestal, he instead imbues them with their intended purpose, inviting visitors not only to use them, but also to partake in a unique conviviality. From the artist's hand, hammered from a small disk of pewter, to the bartender's hand, filled with aromatic bourbon, the visitor's hand, enthusiastically admired, gripped with sweaty palms, and perhaps now rimmed with a red lipstick until washed, the vessel's history of use continues through various user's. As their design, weight, and texture evidence the artist's unique hand, so too will their eventual patina, dents, and dings evidence a rich life after their creation.

-Cecily Hazell

Lamar Dodd School of Art MFA Thesis Catalogue

When his vessels are displayed in a gallery setting, Bosse turns our attention to how they were created. Executed in a variety of materials, the exhibited cups appear identical- a fact that attests to the artist's technical skill and ability to seamlessly recreate the same crafted object by hand. Next to these cups are diagrams cataloguing the process by which they were made: which hammer was used, the hammer's weight, the energy necessitated by this weight, the angle at which the hammer was applied, how many hammer strokes were required. In this way, Bosse not only documents the object's beginnings, but also intimately ties himself to their inception, proclaiming the presence of the artist's hand.

If Bosse is interested in the prehistory of his vessels, he is equally invested in the lives these objects lead upon completion. Those who attended the opening reception of the MFA exhibition were met by a welcome sight: the BOSSE bar. Familiar to many because of its temporary presence a few months earlier on campus, the BOSSE bar served as a much needed respite after long classes, a place where students, professors, and other visitors mingled, periodically swapping cups to gleefully admire the cast metal dinosaurs surrounding the base of one cup or the mustache guard on top of another. Returning visitors fondly reminisced about their first cup, all while Bosse regaled them guests with stories, inspirations, and difficulties surrounding specific vessels. At the Georgia Museum of Art during the opening of the MFA thesis exhibition, visitors could imbibe at the BOSSE bar before and after visiting the show upstairs, where Bosse's cups and diagrams were exhibited amongst the work of his peers. More significant than the drink, though, is the vessel from which it is drunk: a tall vessel of pewter complete with handle, resembling those displayed in the museum. For Bosse, this marks an important continuation of the vessels' lives. Rather than relegate these meticulously crafted functional objects to a pedestal, he instead imbues them with their intended purpose, inviting visitors not only to use them, but also to partake in a unique conviviality. From the artist's hand, hammered from a small disk of pewter, to the bartender's hand, filled with aromatic bourbon, the visitor's hand, enthusiastically admired, gripped with sweaty palms, and perhaps now rimmed with a red lipstick until washed, the vessel's history of use continues through various user's. As their design, weight, and texture evidence the artist's unique hand, so too will their eventual patina, dents, and dings evidence a rich life after their creation.

-Cecily Hazell

Lamar Dodd School of Art MFA Thesis Catalogue